There was iced tea. Always. I don't remember when there wasn't. But I drank my first coffee when I was a young boy sitting on my Granddaddy Barnes' lap. It was perked coffee, sweet with sugar and white with evaporated milk. He was my mother's father and I never remember her parents' kitchen table without a can of Carnation or Pet evaporated milk and a sugar bowl. My grandfather mixed it up in a glass for me while my mother fussed from the other end of the table.

"Coffee will stunt your growth" she said. My grandfather laughed and said, "Men like us don't let women tell us what to do, do we?" My mother laughed. My grandfather stirred.

I was too young to ponder the role bossy women might play in my life, but growth-stunting was something serious to consider. They were a large, noisy family of short people and there always seemed to be someone at the table with a cup of hot coffee. I was determined to be taller than that, I needed to be taller than that, but I didn't want to disappoint my grandfather. "Men like us," he'd said. So I took my chances and drinking coffee didn't stop me from outgrowing them all. I grew taller than my mother while I was still in grade school. When I proudly told my father, he said, "That's not saying much." I outgrew him too.

Eventually my grandfather draped himself in granddaughters (a man raised by his mother, with several sisters, seven daughters and a wife, he always liked girls best) but those times drinking coffee sitting on his lap at the kitchen table are the among the closest I remember feeling to him. He died before I reached high school.

I still drink coffee and sometimes when I have a can of evaporated milk handy I punch two holes in its top with the point of a sharp knife and use it in place of cream. I always think of him when I do. I even remember the way the morning light fell across that long, narrow kitchen and onto the table and my pale glass of mostly milk coffee.

My father's parents, whose house I preferred to visit, were taller people. They were coffee drinkers too, but I never remember sitting on my Grandfather Howerton's lap to drink

| ||

| With my Grandfather Howerton |

But before that happened I had nearly 20 years of Sunday and holiday dinners (lunch to non-southerners) at their house. Every Sunday after church (we all went to the same church a few blocks from my grandparents' house), every Christmas, every Thanksgiving.

When I was a child I ate as a child at Sunday dinner - in the kitchen with my Grandmother Howerton, my sister and eventually my brother, where I belonged. The adults - my grandfather (head of the table), two aunts, two uncles and my

|

| Aunt Beverly and Uncle Sidney |

We were not fancy people and the food we ate was sturdy, plain and tasty but the dining room was formal, the big table, the sideboard, the chairs with upholstered seats. There was a small chandelier. I remember walking through the dining room on the way to the kitchen, looking at what seemed to be the finest and fanciest table I would ever see and longing for the day when I could eat there too. I wanted to eat off the good plates and drink my tea out of the rosy pink glasses. I wanted to feel grown up and grand. And one Sunday, sooner than I ever expected, there was an extra place at the table for me. By then I could eat without spilling and had good enough manners (and dirty looks from my mother if I strayed), but the key to moving up to the adult table in my family was being a

|

| My Aunt Beverly when she was old. |

Eventually I gave up my place at that table and all the other tables of my youth and young manhood and fled, but those pink Depression ware goblets haunted me. I stored them in my memory with care. They were part of the best memories of my youth - after I moved to the big table and before I walked away from the whole family mess.

I grew up with too much family and not quite enough love to hold it all together. My grandfathers were admirable, responsible but emotionally stunted men. One called his wife "Mother" and the other called his wife "Old Lady." Both were abandoned by their fathers - one father ran away and disappeared, the other committed suicide - and were raised by their mothers, tough-minded women who never remarried. They counted on their sons instead. Both men reached adulthood with a sense of responsibility and a profound need for the family they never knew. They both ended up with what they wanted and held on with childlike tenacity as hard as they could for as long as they could. They had to hold on because they never learned to trust the love that is supposed to glue families together. Who knew what might happen if somebody's grip slipped? I am sure it was a frightening thought for them. Maybe their long-gone fathers were to blame, or their mothers, but whatever their reasons for it, they used Sunday dinners and weak coffee, propriety and disappointment, brute force and blood loyalty to get what they wanted. They passed it off as love and passed it on. And it shows. Their sons and daughters, most of them emotionally stunted too - and addicted to God, booze, drugs, anger, whatever got them through - grew to old age never able to escape the long shadows of their fathers or the bondage of their family upbringing. They couldn't love their own children quite enough to set them free. Some of the children's children have escaped but it hasn't been easy.

Shortly after the death of my father last year I acquired the Sunday iced tea glasses. I had asked for them years before, the only thing from my grandparents' house I wanted after they died. I was assured by my sister that they had been secreted away for me to keep them out of unworthy hands. Declarations of worthiness and unworthiness, friendlies and enemies, good relatives and bad, shifting alliances, dishonesty and deceit, secrecy, gossip and outright lies, etc., belong to the mucky, conspiratorial mess of extended family that I escaped years ago and still want no part of. But I always figured that as the eldest grandchild - and the first to make it to the big table - I deserved those Sunday glasses. And I suppose, at last, I was deemed worthy enough by my sister to have them. She enjoys the co-conspiracy of family far more than I do and likes to decide who is worthy and who is not and when and where. She gave me the Sunday glasses after my father's funeral (at the same time she told me I would not be getting a table built by our great-grandfather-the-suicide for his wife and promised to me by my parents years ago. I suppose worthiness has its limits. Besides, what if somebody's grip slips?).

Sometimes the most ordinary things are ritualized and venerated: coffee or iced tea, evaporated milk or the Sunday glasses, old family tables. Grandfathers are denied their complexity and shortcomings and blindly praised. Their children become acolytes and their grandchildren, if they are not true believers awash in the blood of family, are left to question everything and seek love where they can find it. Some have and others haven't.

My Grandmother Howerton brewed Sunday tea in a round Jewel Tea pitcher, my mother had one, I have one too. Theirs came from the Jewel Tea man; mine came from an antique

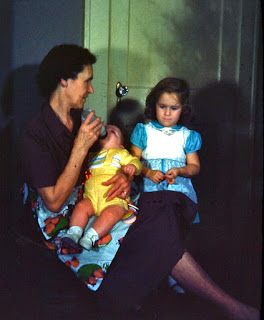

| |

| My Grandmother with my sister and brother. |

I resist ritual and drink my tea out of the Sunday glasses whenever I want to now. They are pink, tapered, short-stemmed, sturdy. I love the way the sugar gathers in the narrow bottom of the glass when I spoon it in. I love the way the sweetness lingers when I munch the melting ice after the tea has been drunk. I've loved those things since I was a little boy at the big table. The Sunday glasses come from that time before the straight bent and the narrow widened, fragile survivors, messengers from the world I once thought I would live in forever, rosy reminders that I could not.