My father believed being gay was a lifestyle choice until the day he died. At least I assume that is true. He died at the age of 91 and I know he believed it until he was past 90. We talked about it on the phone.

And we weren't arguing.

That's important because we spent our lives arguing about one thing or another, the way fathers and sons do when they inhabit lives so different they seem never to have sloshed around the same gene pool. My father was a man of his time and his time had lasted far too long for me. He wanted to hang on to it, I wanted to get on with it. And loud arguing was considered a viable way to have a discussion about anything in my family. Someone was always arguing about something. And old arguments never died. My mother and my father's mother had an ongoing (but non-specific) argument that lasted from the time my mother and father married during World War II until just before my grandmother died in the 1980s. "We made our peace," was all my mother ever said about it after my grandmother died. Some arguments between my parents were so old that they needed only a few fraught words to get things going. It was an efficient way to argue. They reached the really angry part of the fight much more quickly. So much fury, so few words. (The truth is they argued about many things because they had agreed not to talk about the one thing that needed talking about.) My grandmother once told me, "Your mother and daddy have always been mad at something. And your daddy wasn't like that before." Before what? The war? My mother? Before when? She never explained it to me. But it's true. It's who we were. Angry people. Peace was rarely made.

Sometime when my father was around 80 years old we were eating chopped pork barbecue and hushpuppies in a restaurant in North Carolina, pushing each other's buttons about something, most likely the same on stuff - family (always a hot topic), race relations, sexual orientation, sexual relations, Jesse Helms, Jesse Jackson, war and peace, flags and uniforms, Bush and Clinton, politics in general, it could have been anything. He paused, bit the end off a hushpuppy and surprised me. He said he thought there were certain subjects we should never discuss again. My mother, then in the mostly non-verbal stage of her decline, looked stunned, appalled that such a thing had been suggested. But I agreed eagerly. And we didn't.

We stayed on safe ground after that. Basketball was safe ground. North Carolina basketball in particular. Baseball wasn't (I was a lifelong Yankee fan, he hated the Yankees). Stock car racing was safe ground because he was passionate about it and I didn't know enough to argue. Happy family stuff, safe; unhappy family stuff, not. My mother the saintly, safe; my mother the troubled human being, not so much. My nephew the jailbird junkie, NEVER. Weather was always a safe thing to talk about and sometimes it came down to nothing more than that as we picked our way through phone calls every few weeks, especially after my mother died and my father was the only parent I could talk to.

Talking to him could be a chore. My father loved what he called reminiscing and he could do it for hours. He and my mother did a great deal of it, especially during the last years of her life, sorting through photographs, papers. When she couldn't participate any longer he reminisced and she listened. When she was dead he sought out other people, though there had been plenty of other people before that (one of my parents' standing arguments involved all his talk to other people while my mother waited in the car or some other uncomfortable place). He called it reminiscing, but it wasn't. It was much more than that. He pursued the past like a hungry predator because he had so little appetite for the present.

I am not much for reminiscing or predatory pursuit of the past, but it happened sometimes. That's how I brought up the December night we went to meet Gil's body at the train.

It was odd for him to invite me along on such a nighttime errand. My father and I didn't do many things together when I was growing up. Our interests ran in different directions, he worked long hours, we didn't know how to do it as I grew into my teens and beyond. I spent most of the time with my mother, aunts, grandmothers. I always preferred the company of women. Still do. But that night he asked me to ride along with him. I never have been sure why. Maybe he didn't want to be alone and didn't want to say so. Maybe it was because it was my birthday. Maybe he wanted to teach me a lesson (he was tyrannically didactic in the same way he became tyrannically reminiscent later in life). Maybe he wanted to show me something about the way men do things. But he asked me to go with him.

We went downtown to the train station to make sure the corpse of the man who had been his favorite cousin, pal and playmate when he was growing up arrived safely from Florida. I remember seeing the wooden box on a baggage cart on the platform beside the train and again at the funeral home. I remember my father telling the undertaker, "He was a veteran and he will be buried in the veterans' plot." We went home.

The dead man's name was Gil. He was a homosexual ("queer" was the word my dad used relentlessly). He had hanged himself in a closet after an argument with his boyfriend. "I'm not surprised. He chose to live that way and it killed him," my father said. "He hung out around queers and he became one. I warned him." It all was news to me.

My father sounded bitter, angry, betrayed, as if Gil had done something personal to him. And perhaps he had, though my father would never say just how he found out Gil was gay. It was clear in his tone that he believed Gil was an un-man and that that was a dangerous and disgusting thing to be. For years Gil had been a non-person to him. But he lived with us once.

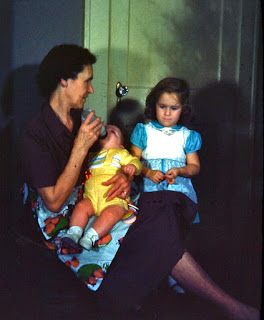

They both served in World War II and after the war my parents and I lived in half of a converted barracks on an old Army base known locally as O.R.D. Gil lived there with us. At least for a while. I remember him as a charming, smiling man in a suit with neatly slicked back hair. I also remember him bearing a strong resemblance to my father. I even have a muddled memory of sharing a bed with him, me under the covers, Gil beside me, sleeping, lamplight shining. Nothing more than that. I was three or four years old. I don't remember any commotion when he left but one day he was gone.

I didn't know about Gil's homosexuality until that winter night in 1963 when we went to meet his body at the train. I had no clear idea what queer meant except that it was a condition that led Gil to kill himself and that my father saw it as a terrible threat and outright danger to unsuspecting boys like me (I told him about a gay man trying to pick me up on Market Street one night and he wanted to go out and find the guy. And do what? Beat him up? Turn him in? We drove around and never found him so I'll never know). He didn't explain the danger. I was sexually stupid for my age. We didn't talk about sex - hetero, homo or otherwise at home (my dad secreted "dirty" magazines in his top dresser drawer and I found them, which is how I first saw Bettie Page and learned about naked women and their strange - not queer, but strange, that was a relief - effect on me).

|

| Bettie Page reading in her high heels and underwear. |

And that is where I was calling from when my father was 90 and I asked about going to meet Gil's body at the train. I had always wondered why my queer-averse father let Gil live with us. Wasn't he afraid that I might end up deciding to be queer too from hanging out around Gil?

"It was after the war. He needed a place to live. He was family," my father said. "I told him he could stay as long as he stayed away from that. He promised he would." I suppose he meant Gil should stay away from whatever passed for gay social life in the late 1940s in the middle of North Carolina. My father seems to have believed that whatever was going on it was happening in Winston-Salem, thirty miles away from where we lived in Greensboro. When Gil broke his promise and couldn't stay away from Winston Salem (that's how my father described it and maybe that's what they called guys fucking guys back then - going to Winston-Salem. There were so many hints and euphemisms.), my father kicked him out. A decade later Gil was dead and we were meeting the train from Florida. It took a long time to understand why we were there.

My father liked the idea that certain things could make a man out of a boy; most of them involved uniforms of one sort or another, flags, salutes, oaths, band music and (best case scenario) combat. He suggested that a few years in the Army might do that for me. I declined and told him I had no interest in Vietnam, hated the fact that other boys my age already were over there fighting and that I didn't think I would go even if they drafted me. Our serious differences had begun by that time. We argued incessantly. But Gil couldn't argue. He was dead in that box. And in the end my father made a man out of him. I know now that is why we were at the train depot that December night. We were man-making.

My father knew how it was done.

He insisted that Gil be buried in the Veterans Circle at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Greensboro. He made all of the arrangements. I don't remember going to the funeral, but I am sure it involved flags and bugles. I have a vague memory of the grave. When I called the cemetery the other day, I was told that Gil would be easy enough to find if I wanted to visit. "All of the veterans' graves have upright stones on them," the woman said, "because that's what they deserve." None of those flat to the ground easy-mow markers like the rest of the cemetery.

And that is where he is. Under his upright stone. Gilmer Wilson Huffines, died Dec. 10, 1963, buried in grave #255 on Dec. 13, 1963, a man among men, no queers allowed.

And that was that.

Gil was back in a world my father approved of, a world as he knew it should be, a world of better days, a world he would try to remake to his narrow specifications, a world he could understand, until he died in 2014 at the age of 91. It was a world no wider than a grave.

----------------------------------------

.JPG)